The War Photographer by Scottish Poet, Carole Anne Duffy (born 1955) is a powerful poem widely used in British schools for young people to reflect on and write about.

This poem by Britain’s Poet Laureate deals with dualities – past and present, one place (war zone) and another (the countryside), awareness and indifference. The inspiration for her poem came from meetings with a war photographer.

War Photographer

In his darkroom he is finally alone

with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.

The only light is red and softly glows,

as though this were a church and he

a priest preparing to intone a Mass.

Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.

He has a job to do. Solutions slop in trays

beneath his hands which did not tremble then

though seem to now. Rural England. Home again

to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel,

to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet

of running children in a nightmare heat.

Something is happening. A stranger’s features

faintly start to twist before his eyes,

a half-formed ghost. He remembers the cries

of this man’s wife, how he sought approval

without words to do what someone must

and how the blood stained into foreign dust.

A hundred agonies in black-and-white

from which his editor will pick out five or six

for Sunday’s supplement. The reader’s eyeballs prick

with tears between bath and pre-lunch beers.

From aeroplane he stares impassively at where

he earns a living and they do not care.

The first stanza of six lines reminds us of the loneliness of the war photographer in the darkroom as he develops his photographs of war and the terrible suffering he has witnessed. His past and present come together in the darkroom.

There is suffering in every frame of every spool (with 36 photographs to every spool). His only light in the room to see is the red light. The red is a reminder of the blood and pain that he has witnessed on the battlefield and in towns and villages. The loneliness of the darkroom reminds the photographer of the wars he has photographed in Belfast in northern Ireland, Beirut in the Lebanon and Phom Penh in Cambodia.

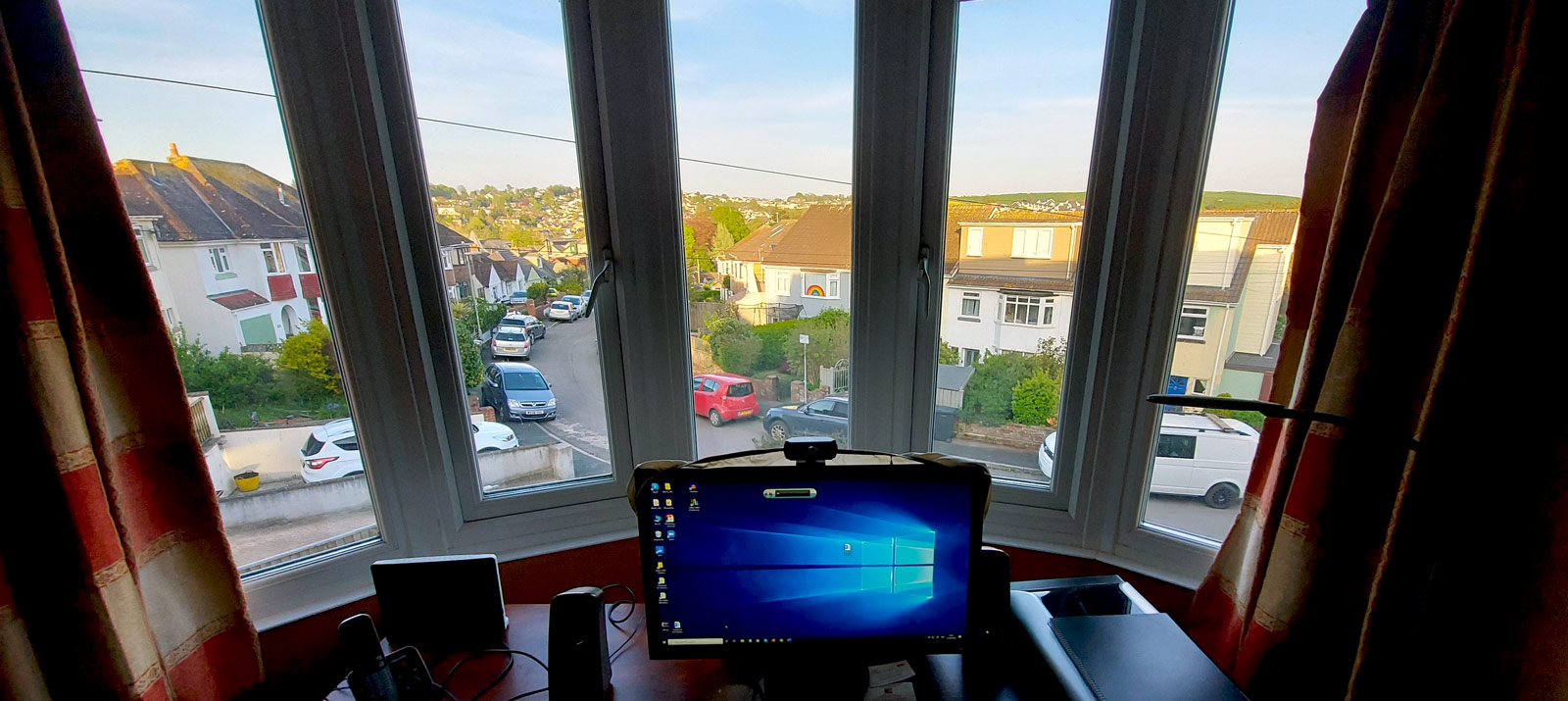

The poet compares the war photographer to a priest who mindfully prepares everything to offer up for his religious service. The war photographer mindfully prepares to develop in the tray of liquid for the prints to become clear. She writes that All flesh is grass. The underlying message here is that he can probably see his garden and fields are nearby but the lonely photographer suffers when he remembers the wounds on people’s flesh in the war zones while the grass outside his home in England reminds him of his painful memories.

The second stanza tells us the war photographer has a job to do. This means he must let go of his painful memories of war and get back to the work of developing his photographs. He wants to be in the present moment but his hands tremble due to memories of the painful war zones he has witnessed. He is home again only to have to deal with the smaller difficult issues like the weather. In the present moment, he can then look out on the grass of the fields, watch the weather change, and know that the children can play together in the summer heat without being maimed or killed by landmines or shells. The poet reminds us not to let the painful past act as a dark shadow over the present.

The third stanza refers to the war photographs appearing on the print in the tray of solutions developing his photograph. Once again, the mind of photograph goes back to his painful memories. The photograph gradually comes through onto the print like a half formed ghost of the dead man’s photograph. He remembers the man’s wife. He had asked for her approval to take the photograph of her dead husband. He saw in the photograph the blood seeping into the earth of the dead man. It is such a contrast for him between the war zones and the countryside in England where the children play outdoors and people talks about the changes in the weather. The past and the present seem like different worlds.

In the fourth and final stanza, he knows the process. The editor will pick out five or six photographs to publish from the his 100 photographs of war. He knows the readers of the Sunday newspaper will look at the photographs on Sunday morning between having a bath and a beer at lunchtime. Some readers will have tears in their eyes at seeing the newspaper photographs but he knows the readers really do not care about suffering of the victims in war zones. The readers live in the small world – unlike the photographer who knows the world of war and the world of baths and beer.

The photographer wants his readers to wake up and to stop the war. He sits on the plane to go to the next war zone rather depressed. The war photographer wants to change the world but he cannot.

May our hearts be rich in love and compassion

May we have the capacity to respond to the suffering of others

May wise and compassionate words and actions be linked together